- Home

- Jodi Picoult

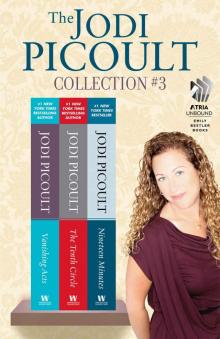

The Jodi Picoult Collection #3 Page 9

The Jodi Picoult Collection #3 Read online

Page 9

I tell him this, and he laughs. “I know what you want, grilla,” he says, and then he swings me into his arms and so high that the sun kisses blisters onto the soles of my feet.

* * *

Arriving at Sky Harbor Airport is, I imagine, like landing on Mars—jagged mountains and blood-red soil as far as I can see. I step out of the double glass doors and walk into a solid wall of heat. I wonder how a place like this and a place like New Hampshire could possibly be part of the same country.

There is already a message on my cell phone from Eric—an address, actually. The lawyer sponsoring him to try a case in this state is an old classmate from law school, and someone—his secretary’s cousin’s friend, or something equally as complicated—has agreed to let us stay in her house while she moves in with her boyfriend.

I collect a skittish Greta from the oversized-baggage area, rent an SUV (How long do you need it? the clerk had asked, and I had stared at the woman blankly), and pile our luggage into the backseat and trunk around the collapsible dog cage. Going through the motions only reminds me of the thousand things I don’t know: what the grocery store chains are out here; how to get to this house on Los Brazos Street; when I will see my father again. Sophie’s backpack slips to her elbows, her hand rides on the taut pull of Greta’s leash. She follows me, bouncing on the balls of her feet, trusting me to know where we’re going.

Don’t all children?

Didn’t I?

We follow the Avis representative’s directions, passing more stores and shopping malls than there are in all of New Hampshire. There seems to be a supplier for everything you might ever want or need—sushi, motorized scooters, bronze sculpture, paint-your-own ceramicware. I feel absolutely lost out here, and that, actually, is a relief. In Arizona I am not supposed to know anything; this is all naturally foreign. Unlike Wexton, here I have the right to wake up in the morning and not remember who or where I am.

The address Eric has given me is in Mesa, and must be a mistake. The only residences on Los Brazos are in a trailer park—not one filled with tidy rows of compact, immaculate homes with little gardens and window boxes, but something that resembles an enormous junk heap. There’s a dusty parking lot encapsulating fifty motor homes, none numbered, all in various states of disrepair. Sophie kicks at the back of my seat. “Mommy,” she asks, “do we get to live in a bus?”

We drive past an old woman standing at the entrance of a trailer park, wrapped tight in a long raincoat in spite of the heat. Inside the fence, there doesn’t seem to be a single living soul. I imagine how hot it must be to live inside a metal trailer, when the outdoor temperatures alone break a hundred degrees.

We’ll stay in a hotel, I decide, but then I remember that we don’t have enough money for that. Eric said that this might not be a matter of weeks, but months.

Some of the trailers have cacti planted next to their steps. Some have bronze garden ornaments stuck in the stones along their foundations. A young woman steps out of her door, and I immediately roll down my window. “Excuse me!” I call out. “I’m trying to find . . .” I look down at the number Eric left in his message.

“No hablo inglés.” She hurries back inside her trailer, and pulls shut all the curtains so that we cannot peek inside.

I would drive to Eric, but he hasn’t told me where he is. Before I know it, I’ve made a full circle through the motor home community, and I’m back on the driveway that leads out to the main road. The old woman is still standing there, and she smiles at me. She has the lined maple skin and moon face of a Native American; her short white hair is twisted into a red scarf on top of her head. Every one of her fingers is decorated with a silver ring, something I notice when she flashes us by pulling aside the lapels of her coat. Underneath, she is wearing a T-shirt that says DON’T WORRY, BE HOPI, and various items are anchored to plastic loops sewn into the satin lining of the jacket—rusted silverware, old 45s, and about ten Barbie dolls. “Garage sale today,” she says. “Extra cheap!”

Sophie’s face lights up when she sees the dolls. “Mommy—”

“Not today,” I say, and I smile tightly at the woman. “Sorry.”

She shrugs and closes her coat.

I hesitate. “Do you by any chance know which trailer is number 35677?”

“It’s right over there.” Pointing, she indicates a decrepit building less than twenty feet away. “Nobody lives in it, though. Girl moved out a week ago. The neighbor’s got the key.”

The neighbor’s trailer has all kinds of rainbow windcatchers suspended from the overhang of the doorway. A stool with a mosaic seat and plaster-sculpted human legs and feet supports a twisted cactus whose shoots look like the tangled map of the New York subway. Hundreds of brown feathers are tied with string and leather to the green branches of a paloverde tree in the front yard.

“Thanks,” I say, and telling Sophie to wait in the car, I leave the air-conditioning running and walk up to the door. I ring the bell, twice, but there’s no answer.

“They’re not home,” the old woman says, as if I haven’t figured this out for myself. But before I can reply, I hear the approaching whine of a police siren. Immediately, I am back in Wexton, ten seconds before my entire life fell apart. I run for the car, for Sophie.

The police cruiser pulls in behind my rental, but when the officer gets out, he walks away from me and toward the old woman. “Now, Ruthann,” he says, “how many times do I have to tell you?”

She tightens the belt of her trench coat. “Halíksa’i, you can’t tell me what I can’t do.”

“This property isn’t zoned commercial,” the policeman says.

“I don’t see anyone selling anything.”

He flips up his sunglasses. “What’s under your coat?”

She turns to me. “That’s sexual harassment, don’t you think?”

The officer seems to notice me for the first time. “Who are you? A customer?”

“No, I’m just moving in.”

“Here?”

“I think so,” I explain. “I was looking for my key.”

The policeman pinches the bridge of his nose. “Ruthie, get yourself a table at one of those Indian flea markets, okay? Don’t make me come back here.” He gets back into his car and zooms down the block again.

The old woman sighs and trudges up to the front door that I’ve been knocking on. “Hold your horses,” she says, “I’ll get your key.”

“You live here?”

She doesn’t answer, just unlocks the door and walks in. Even from this distance, the house smells like sugar burning. “Well?” she calls after a minute. “Come on.”

I get Sophie and Greta out of my car, and tell the dog to wait on the stoop. As Sophie and I step inside, Ruthann takes off her trench coat and spreads it over the back of a futon, the heads of the Barbies inside poking out like gophers. Nearly everywhere I look, there is some box of junk or a tin of beads and feathers; glue guns lay like discarded murder weapons on the floor. “I know it’s here somewhere,” she says, rummaging in a drawer full of twigs and pencils.

Behind me, Sophie slides one of the dolls out of its resting place in the coat. “Mommy, look,” she whispers.

This Barbie doll has a miniature pint of chocolate ice cream in one arm and a Sleepless in Seattle video in the other. She wears sweatpants, fuzzy slippers, and has a gun strapped to her hip. A tag around her neck reads PMS Barbie.

It makes me laugh out loud. I reach into the trench coat and pull out another doll, Reality TV Barbie. She is wearing a jog bra and wedding veil and is holding a map of the Amazon. She has a half-eaten sheep’s eye in her mouth, a fistful of dollars in her back pocket, and a Nike contract tucked into her athletic sock.

“These are very funny,” I say.

“I call them Black Market Barbies. Dolls for girls who don’t want to stop playing yet.” The old woman crosses the room and holds out her hand. “I’m Ruthann Masáwistiwa, owner and CEO of Second Wind, specializing in possession reincar

nation.”

“What’s that?”

“Finding homes for what other folks don’t want. I’m one big portable Indian pawnshop.” She shrugs. “Your old toaster might be someone else’s in-box at work. Your cowboy boot could have a whole next life as a planter for geraniums.”

“What about the dolls?”

“Another rebirth,” she says proudly. “I make them, down to every last accessory. Even the Prozac prescription bottle for Mid-Life Crisis Barbie. I wanted to carve katsina dolls, but only Hopi men can do that—women are supposed to carve with their wombs, if you get my drift. Then again, I don’t like being told what not to do.”

I shake my head, trying to follow this conversation. “Katsina . . . ?”

“They’re spirits, to the Hopi. There are hundreds of different ones—male, female, plants, animals, insects—you name it. They used to visit in person, but now they come as clouds, or up through the earth, for ceremonies that bring rain and snow to the crops, and blessings. Katsina dolls are carved out of cottonwood, to give to children at these dances so they can learn the religion, but nowadays they’re also a hot-ticket item for collectors.” Ruthann picks up one of her Barbies. “Don’t know if this’ll have the same staying power, but I’m trying.” She reaches onto a shelf and pulls down a Kelly doll, Barbie’s little sister, which she offers to Sophie. “Bet you’d like this,” she says.

Sophie immediately sits down on the floor and begins to pull off Kelly’s elastic clothes. “I have a Kelly at home.”

“Ah. And where’s that?”

“Next door,” I interrupt. I am not ready to tell this woman our story yet. I don’t know that I’ll ever be ready.

Ruthann squats down beside Sophie and pretends to pull out of her ear a long, red shoelace. It reminds me so much of my father, doing his magic tricks at the senior center, that tears line the column of my throat. “Well,” Ruthann says. “Will you look at that.”

At the end of the shoelace is a key. Ruthann cups her hands around Sophie’s tiny face. “You come play with my dolls whenever you want, Siwa.” Then she gets to her feet slowly and presses the key into my palm. “Don’t lose it,” she warns.

I nod. I think of all the ways I might interpret those words.

* * *

It takes two people to make a lie work: the person who tells it, and the one who believes it. The first lie my father must have told was to me—that my mother had died in a car crash. But why didn’t I ask, when I was old enough, to visit her grave? Why didn’t I question the fact that I had no maternal grandparents or uncles or cousins who ever visited? Why didn’t I ever look for my mother’s jewelry, her old clothes, her high school yearbook?

There were times when Eric was drinking that he’d come home, too careful in his movements to not be intoxicated. But instead of calling him on his bad judgment, I’d pretend everything was fine, just like he was doing. You can invent any fiction and call it a life; I thought that if I did it often enough, I might start to believe it.

Sometimes, when you don’t ask questions, it’s not because you are afraid that someone will lie to your face.

It’s because you’re afraid they’ll tell you the truth.

* * *

There are bonuses to this trailer: you can walk the entire length of it, four times, in a single breath. You can stand in the kitchen and see into the bedroom. The kitchen table cleverly converts into an extra bed. To Sophie’s delight, the entire interior is painted Pepto-Bismol pink, down to the toilet seat.

There’s a phone book.

There are seventy-seven listings for “Matthews” in the Greater Phoenix Region. Thirty-four live in Scottsdale. Just as the operator told me, there’s no Elise Matthews, no E. Matthews, nothing that I could trace to my mother. It is entirely possible that she’s become a different person, too.

The previous occupant, in a fit of mercy, has left behind an oscillating fan. I set it up in the bedroom, pointing directly at Sophie and Greta, who have curled up on top of the double mattress. Then I step outside and sit on the stoop. It is still blistering hot, although the sun has nearly set. The sky seems wider here, stretched like cellophane, and the stars are starting to come out. I am convinced they are a puzzle. If I stare at them hard enough, they’ll move of their own accord; they will link their sharp arms and spell out all the answers.

We say it all the time—how we’d give up anything for someone we love—but I wonder, when push comes to shove, who’d truly step up to the line. Would Eric jump in front of a bullet to save me? Would I do it for Eric? What if it meant I’d die, or be paralyzed forever? What if it meant that I could never go back, that my existence would be divided from that point on into before and after?

The only person I can honestly say I’d save without a second thought is Sophie, simply because in the accounting scheme of my heart, her life means more than mine.

Had my father felt that way, too?

I take out my cell phone and dial Fitz, but his voice mail picks up. I dial Eric, and he answers. “Where are you?” I ask.

“Looking at the most amazing view,” Eric says, as an unfamiliar car pulls in front of me. Eric leans out the window, still holding the phone to his ear. “Want to hang up now?” he asks, and he smiles.

He gets out of the car, and I fall into his arms, the first place all day that feels familiar. “How’s Soph?” he asks.

“Sleeping already.” I follow him as he starts into the trailer to find her. “Did you see him?”

Eric doesn’t have to ask who I’m talking about. “I tried. But the Madison Street Jail won’t let me in without a Bar card.”

“What’s that?”

“A little piece of paper that doesn’t exist in New Hampshire, which says I’m in good standing with the state Bar association.” Eric stops dead in the entryway, staring at the pink couch and the cotton candy wallpaper. “Jesus Christ, we’re living inside a Hubba Bubba bubble.”

“I was thinking more like the Barbie Winnebago,” I say. “What about me?”

“What about you?”

“Would they let me in to see him?”

On Eric’s face, I see a play of responses: his reluctance to let go of me, now that we’re both here; his fear of what I might find; his understanding that I need my father, right now, more than I need him. “Yes,” he says. “I think they would.”

* * *

I don’t know why it’s called “getting lost.” Even when you turn down the wrong street, when you find yourself at the dead end of a chain-link fence or a road that turns to sand, you are somewhere. It just isn’t where you expected to be.

Twice, I pass exits on the highway for Downtown Phoenix and have to turn around. Three times, I stop at a gas station to ask for directions. How hard can it be to find a jail?

When I finally arrive, I am surprised by how ordinary it is on the inside: the serviceable tile and banks of plastic chairs. This could be any state agency. I wonder if there are visiting hours I should have called for in advance. But there are other people in the lobby area—lanky black boys wearing baggy pants, Native women with tears still drying on their cheeks, an old man in a wheelchair with a toddler riding on his lap. I follow the lead of everyone else, taking a form from a stack on a table. They are simple questions, or would be for anyone not in my situation: name, address, DOB; relationship to the inmate; inmate’s name. I take a pen out of my pocket and start to fill it out. Delia Hopkins, I write, and on second thought, cross it out. Bethany Matthews.

After I finish, I stand in line, trying to pretend it is any other familiar queue: the line at the grocery store; the line of parents waiting in their cars to pick up children after school; the wait to sit on the lap of a mall Santa Claus. When it is my turn, the officer looks at me. “First time?”

I nod. Is it that obvious?

“I need your ID, too.” He does a double-take at my New Hampshire license, but enters the information into his computer. “Well,” he says after a moment of watching the scr

een, “you’re clear.”

“Of what?”

“Outstanding warrants for arrest.” He hands me a visitation pass. “You want to head to that door on the left.”

I am told to pick any free locker behind me and put all my personal belongings inside. Then comes a metal detector and an elevator ride, and when the doors open, I realize where they have been hiding this jail. It is large and gray, intimidating. There are echoes: steel striking steel; a man screaming; an intercom. An inmate holding a washcloth up to his eye walks by in the company of two officers, who step into the elevator we vacate. More officers sit inside a glass booth, monitoring our progress as we are led to the visiting room.

Inside are four booths, each divided by a line of reinforced glass, a telephone intercom on each side. Round metal stools are bolted to the floor, evenly spaced like the spruces at a Christmas tree farm. There are other people waiting here, too: a woman in a burka, a teenager with an angry scar across his cheek, and a Hispanic man whispering a rosary.

My father is the last prisoner to be brought in. He is wearing striped scrubs, just like you’d see in a cartoon, and for the first time this becomes real to me. He is not going to step forward and pull off the costume, tell me this has all been a bad dream; it is really happening; it is now my life. My hand comes up to my mouth, and I know he can’t hear me draw in my breath like I’m drowning, but he touches the glass between us all the same, as if it might still be that simple to reach me.

He picks up the phone and mimes for me to do the same. “Delia,” he says, his voice hammered thin. “Delia, baby, I’m sorry.”

I’ve told myself that I won’t cry, but before I know it, I’m doubled over on the tiny stool, sobbing so hard that my chest hurts. I want him to reach through the glass like the magician I used to think he was and tell me this is all just a misunderstanding. I want to believe whatever it is he has to say.

“Don’t cry,” he begs.

I wipe my eyes. “Why didn’t you tell me?”

Small Great Things

Small Great Things Leaving Time

Leaving Time Nineteen Minutes

Nineteen Minutes Larger Than Life

Larger Than Life Perfect Match

Perfect Match My Sister's Keeper

My Sister's Keeper The Pact

The Pact Handle With Care

Handle With Care Songs of the Humpback Whale

Songs of the Humpback Whale Mermaid

Mermaid The Tenth Circle

The Tenth Circle The Color War

The Color War Leaving Home: Short Pieces

Leaving Home: Short Pieces House Rules

House Rules Lone Wolf

Lone Wolf The Storyteller

The Storyteller The Book of Two Ways

The Book of Two Ways Shine

Shine Off the Page

Off the Page Sing You Home

Sing You Home Second Glance: A Novel

Second Glance: A Novel Mercy

Mercy Vanishing Acts

Vanishing Acts Between the Lines

Between the Lines Plain Truth

Plain Truth Salem Falls

Salem Falls Keeping Faith

Keeping Faith Harvesting the Heart

Harvesting the Heart Change of Heart

Change of Heart Where There's Smoke

Where There's Smoke Leaving Time: A Novel

Leaving Time: A Novel Over the Moon

Over the Moon House Rules: A Novel

House Rules: A Novel The Jodi Picoult Collection #2

The Jodi Picoult Collection #2 Leaving Home: Short Pieces (Kindle Single)

Leaving Home: Short Pieces (Kindle Single) My Sister's Keeper: A Novel

My Sister's Keeper: A Novel![Mermaid [Kindle in Motion] (Kindle Single) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/03/mermaid_kindle_in_motion_kindle_single_preview.jpg) Mermaid [Kindle in Motion] (Kindle Single)

Mermaid [Kindle in Motion] (Kindle Single) The Jodi Picoult Collection #4

The Jodi Picoult Collection #4 Sing You Home: A Novel

Sing You Home: A Novel The Jodi Picoult Collection

The Jodi Picoult Collection Lone Wolf A Novel

Lone Wolf A Novel Second Glance

Second Glance Larger Than Life (Novella)

Larger Than Life (Novella) The Jodi Picoult Collection #3

The Jodi Picoult Collection #3